🍊 Friday Gazette: July 18, 2025

One year after Hawarden, six artists join city residency and UCR soccer opens with Big Ten games.

This week, as pomegranate season peaks and trees all over Riverside are bowed over with heavy fruit, Seth learns about a project at UCR that aims to diversify the world of pomegranates with research into varied and delightful cultivars beyond the Wonderful.

There are two types of people in Riverside: those who have fruit trees and can’t use up all their harvest, and those who eye that bounty with jealousy, spending the harvest season thinking of ways to wheedle their way into acquiring a share from their neighbors’ groves. The haves and the have-nots, if you will.

When I was in Chicago, I was one of the haves—my backyard boasted a sour cherry tree, raspberry canes, and a giant strawberry patch. I had a standing order with Amazon.com for more half-pint jars to store all the jam I made from the fruit I failed to unload on my neighbors. Since arriving in Riverside, however, the shoe has been on the other foot, and I’ve converted to a gleaner—from have to have-not.

I maintain a mental map of avocado trees on my dog-walking route whose fruit-laden branches overhang the sidewalk, and I know three different spots where kumquats dangle in the public right-of-way and are, therefore, fair game for a quick snack. My friends and neighbors know I’m on the prowl, and when the season is in full swing, I’m on speed dial to absorb excess grapefruit, apricots, and persimmons. I haunt the neighborhood buy-nothing group on the lookout for tangelos, temple oranges, and lemons for my annual marmalade run.

Right now, pomegranate trees are in full fruit. I have a neighbor, Bob, who saw me this week while I was out walking the dog and got a gleam in his eye. “Say, Seth, could you use any pomegranates? My wife’s already made seven batches of jelly, and I’ve got six more bags of fruit I’m trying to unload.” I apologized: “Bob, I’m already committed to taking excess pomegranates from my buddy Bill’s trees. My fridge can’t accommodate any more.” Bob told me he understood. He rolled up his sleeve and showed off scratches and scabs all over his forearm, earned from the thorns and brambles of his pomegranate branches. “I know I’m not supposed to hate a tree, but I sometimes hate my pomegranate—it tears up my arms every year and produces more fruit than I can ever use.” I backed away slowly and nodded sympathetically before he could press any fruit into my hands.

I feel for Bob. Not enough to take his extra pomegranates, but I get it. Being one of the bounteous fruit-havers is not all happiness and light—it can be a weighty responsibility. Even if you like pomegranates, the sheer quantity of fruit that a mature tree produces can be overwhelming. Another afternoon hunched over the sink, picking arils from those rosy globes! Another round of pre-treating stains on your aprons where drops of scarlet juice invariably land. It’s a lot. Pomegranate monotony is real.

But what if it weren’t? What if there were as many pomegranate varieties as there are apples or oranges? What if you could choose a pomegranate to suit your mood or even your color palette?

My friend Norm (who also writes a regular column for the Gazette) turned me on to an opportunity to expand my pomegranate horizons when he shared an announcement from UCR’s Plant Biology department. Pomegranate researchers were seeking participants for a pomegranate tasting that would inform their research into breeding new pomegranate varieties. I leapt at the chance, filled in the Google form, and presented myself at the appointed time to do my tasting.

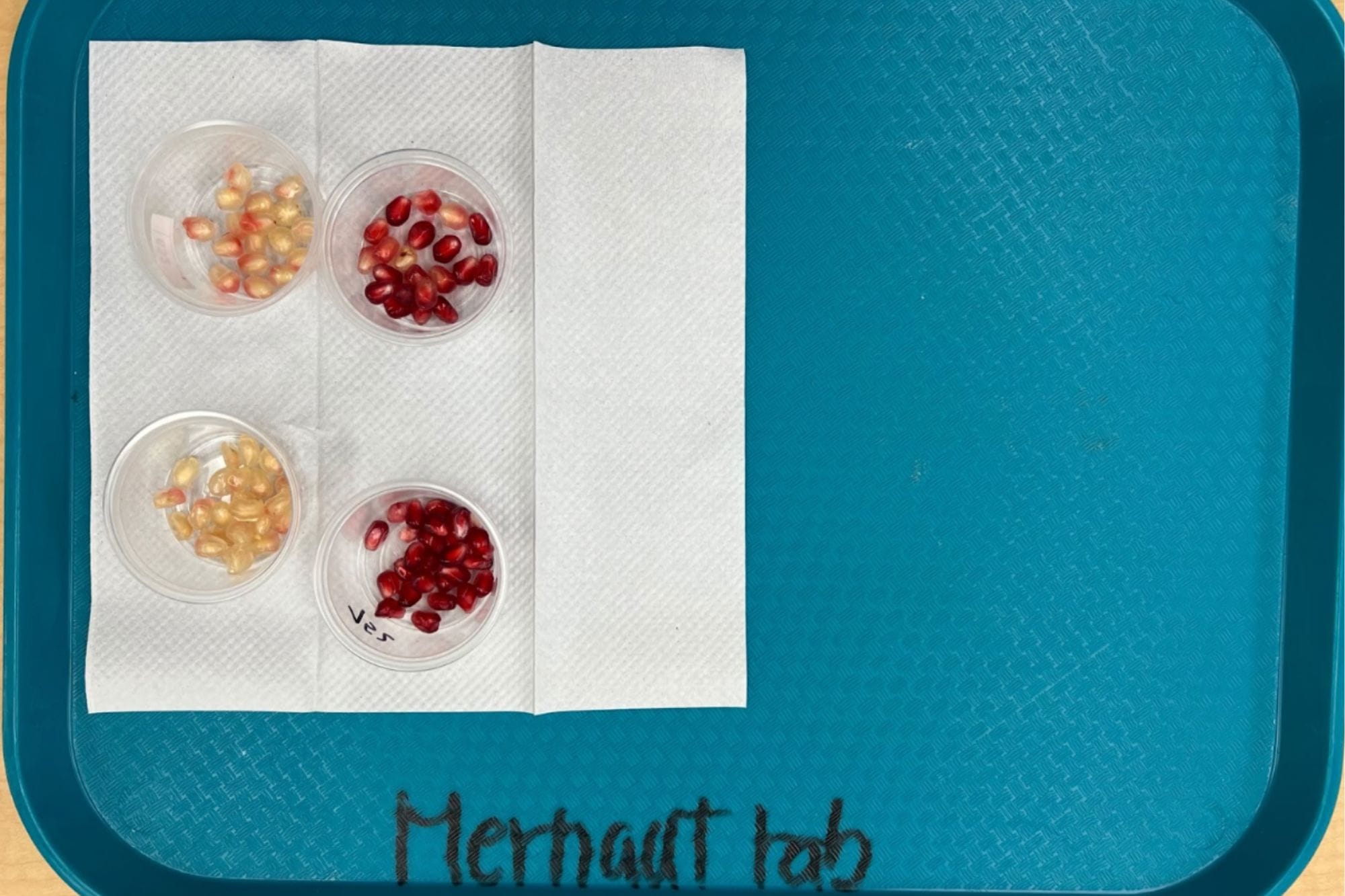

The tastings take place in the lobby of Batchelor Hall, under the watchful eye of UCR’s pomegranate research brain trust: Mariano Resendiz and Ryan Traband, two grad students at varying stages of their doctoral programs. A team of undergraduates assists with the research; on that particular day, they were on aril duty, painstakingly removing the kernels of edible fruit from four different types of pomegranates and portioning them into numbered sample cups for taste-testers to try.

Tasters sample each variety and then record their reactions in an online form, rating the desirability of each type according to several categories: sweetness, sourness, bitterness, color, texture, and the overall experience of eating each kind.

Just the color variation alone is shocking! If you’re like me, you’ve only ever eaten one kind of pomegranate, the cultivar named “Wonderful.” Wonderful pomegranates account for 90% of all U.S. pomegranate production (of which 95% happens in the great state of California). So we think we know what a pomegranate should look like: magenta/purple skin, deep purple/red fruit, with juicy flesh and crunchy seeds. But even with only four varieties, the range of pomegranate possibilities suddenly expanded for me. The pale translucent arils packed a punch, and even the darker-colored fruit offered a range of astringency and sweetness.

The data collected during the tasting sessions is regressed, analyzed, and summarized by Resendiz, Traband, and their team. The goal of this part of their research is to produce meaningful data about the relative appeal to consumers of different kinds of pomegranates. The tasting data will be paired with chemical analyses of each variety.

Eventually, they hope to use all this data to support the breeding of new varieties of the fruit and to diversify pomegranate production worldwide—not only to provide consumers with new experiences but to contribute to the survival of pomegranates going forward. The current monoculture in pomegranate production leaves the industry at risk if environmental catastrophe, pests, or disease decimate the Wonderful variety. Resendiz and Traband hope their research will safeguard the future of this agricultural sector.

They’re also interested in the genetic components that contribute to the “nutraceutical” qualities of pomegranates and their juice. By identifying exactly what chemical components and genetic markers create the antioxidant effects of pomegranate consumption, they’ll be able to select for conditions to enhance those health benefits.

I tasted four types during the experiment: Wonderful (the dominant pomegranate that we all know), Eversweet, Chater, and Phoenicia. Chater is a pleasant and innocuous fruit with familiar red arils and a mild, refreshing flavor. Eversweet and Phoenicia boast pale pink to translucent white arils. Phoenicia has a bracing astringency and an intense sour edge, while Eversweet is milder and pleasant.

Those four varieties are only a portion of the cultivars being studied at UCR. I toured the experimental grove near Chicago Avenue and Martin Luther King Boulevard with Resendiz and Traband, where 15 different pomegranate types are represented, each with several trees. The team studies the fruit over years of cultivation, comparing varieties for disease resistance and performance under the stresses of real-life climate ups and downs. They are following in the footsteps of Dr. John Chater, who planted these groves and initiated this research in 2010 as a UCR grad student before leaving to become a professor at the University of Florida.

While we strolled among the rows, I confessed to Resendiz that I hadn’t really detected any bitter notes in any of the four types of pomegranate sampled in the tasting. “Huh! It could be that you’re not able to taste bitter flavors! I wondered if I should have had experimental subjects lick a strip of PTC paper to calibrate the bitterness scores—it helps identify people who have an inherited sensitivity to bitter flavors…” Traband chimed in, “Yeah, do you really love dark chocolate? That could mean you have a congenital inability to discern bitterness.” Resendiz agreed, “Maybe next year, when we repeat the tastings, we’ll add that wrinkle to our analysis.”

A few other varieties tasted in the field provided even more interesting fodder for comparison. Traband showed me the Parfianka. He calls this variety a prima donna of a tree: magnificent when conditions are perfect, but difficult to manage due to its temperamental sensitivity to adverse growing conditions and a hyper-short harvest season. Its seeds are soft and chewable, almost the texture of a sunflower seed, so there’s no unpleasant crunch when you bite down. “It’s a Ferrari, not a Honda Accord,” Traband says.

The Desertnyi pomegranate has a light orange rind and a delightful sourness—almost like a Sour Patch Kid. Even further down the sour path is the putatively inedible Haku Botan ornamental pomegranate, whose clear yellow/white arils are as tart as pure citric acid—the Sour Warhead of the pomegranate world. I choked on its astringent bite but would eat it again in a heartbeat.

The day after our tour, Resendiz, Traband, and their team of undergrads went back to the fields to harvest all the remaining fruit from the experimental pomegranate grove. They’ll sort and measure the fruit, weigh it, and then juice it to perform comparative chemical analyses of the varieties, feeding the data into the multi-year breeding program research catalog. Will there be lots of leftover juice? “Probably not,” says Resendiz, “but we will have plenty of fruit to spare to make pomegranate juice for ourselves and our staff.”

The pomegranate research team at UCR is small, especially compared to the legions of scientists on campus studying citrus, but the work they’re doing is vital and fascinating, at the intersection of capitalism and ecology. It can be difficult, Resendiz tells me, to find financial support for academic fruit breeding programs like UCR’s. The Wonderful Company (which grows, markets, and produces nearly all of the commercially available pomegranates in the U.S.) has occasionally funded their research in the past but tends to focus its R&D investment on UC Davis’s larger pomegranate research wing.

As a parting question, I asked Resendiz and Traband if they were aware of any restaurants in Riverside using pomegranates in a creative and delicious way. Nothing sprang to mind, but Resendiz recommended I keep my eyes peeled for chiles en nogada on Mexican menus, especially during the winter season—a traditional recipe for poblano peppers stuffed with meat and pomegranate arils that’s usually topped with a savory walnut sauce. Traband endorsed making your own Grenadine syrup by reducing fresh pomegranate juice with sugar. And I can personally recommend making jelly from pomegranates and apples—the apples provide the pectin, and the pomegranate adds complexity and tartness.

Are you curious to try out more pomegranate varieties? This year’s UCR pomegranate tastings are done, but the Plant Biology department posts events periodically on UCR’s event calendar. Last week, there was a comparative avocado oil tasting, which I was sad to miss, but I’ll be attending more in the future as they pop up.

How do you use up your pomegranates? Are you one of the bounteous Riversiders, or are you a gleaner like me? Have you had a memorable pomegranate dish in a Riverside restaurant? Tell me about it—email seth@raincrossgazette.com with all your pomegranate wisdom!

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every morning. For free!