Drone Crackdown on Illegal Fireworks Yields 65 Citations, $97,500 in Fines

New aerial surveillance program shows mixed results across neighborhoods as complaints increase.

At the heart of Riverside’s bustling transit system, Magnolia Tower once stood as a pivotal junction, orchestrating the flow of streetcars, trains, and automobiles through the growing city.

The Riverside and Arlington Railway, a brainchild of the visionary Frank A. Miller of the Mission Inn, was instrumental in ferrying passengers between downtown Riverside and the Arlington area. Initially, the cars were drawn by horses or mules, but by 1900, the line was electrified, marking a significant milestone in the city’s transportation history.

The Salt Lake Route Railroad, a pivotal development in 1904, intersected with the Riverside and Arlington lines at Brockton Avenue, marking a significant point in the city’s transportation network. A shelter shed was erected for passengers at this intersection, a tangible symbol of the growing importance of transportation in Riverside’s development. Henry Huntington, a close associate of Frank Miller, gained control of Riverside and Arlington in 1903. By 1911, he had merged several of his acquired lines into his Pacific Electric, further shaping the city’s transportation landscape.

1914 marked another significant change. The city of Riverside, in late 1912, completed the ambitious construction project of the fill across the Tequesquite Arroyo, directly connecting Magnolia Avenue at Fourteenth Street and Market Street. This new development paved the way for a more direct route, as Huntington moved his streetcar from Brockton Avenue to a straighter line down the new Magnolia Avenue with the plan to extend to Corona. The first PE car across the new fill on New Magnolia Avenue was on Friday, June 5, a momentous occasion that accommodated riders to attend a performance of the play “Zarageuta” by the boys at Poly High School, marking a new era in the city’s transportation history.

However, with the new crossing and the anticipated increase in traffic, safety measures were a pressing concern. Various solutions were proposed, including lowering the Salt Lake Route’s grade and building an underpass under Magnolia Avenue. This was considered a more cost-effective option to go under the Salt Lake track as the Pacific Electric and other traffic on Magnolia was much more than on the Salt Lake Route. The estimated cost in 1914 to build the Salt Lake Route track underpass was approximately $100,000. This was a significant sum at the time, making this solution impractical and highlighting the complexities of transportation planning.

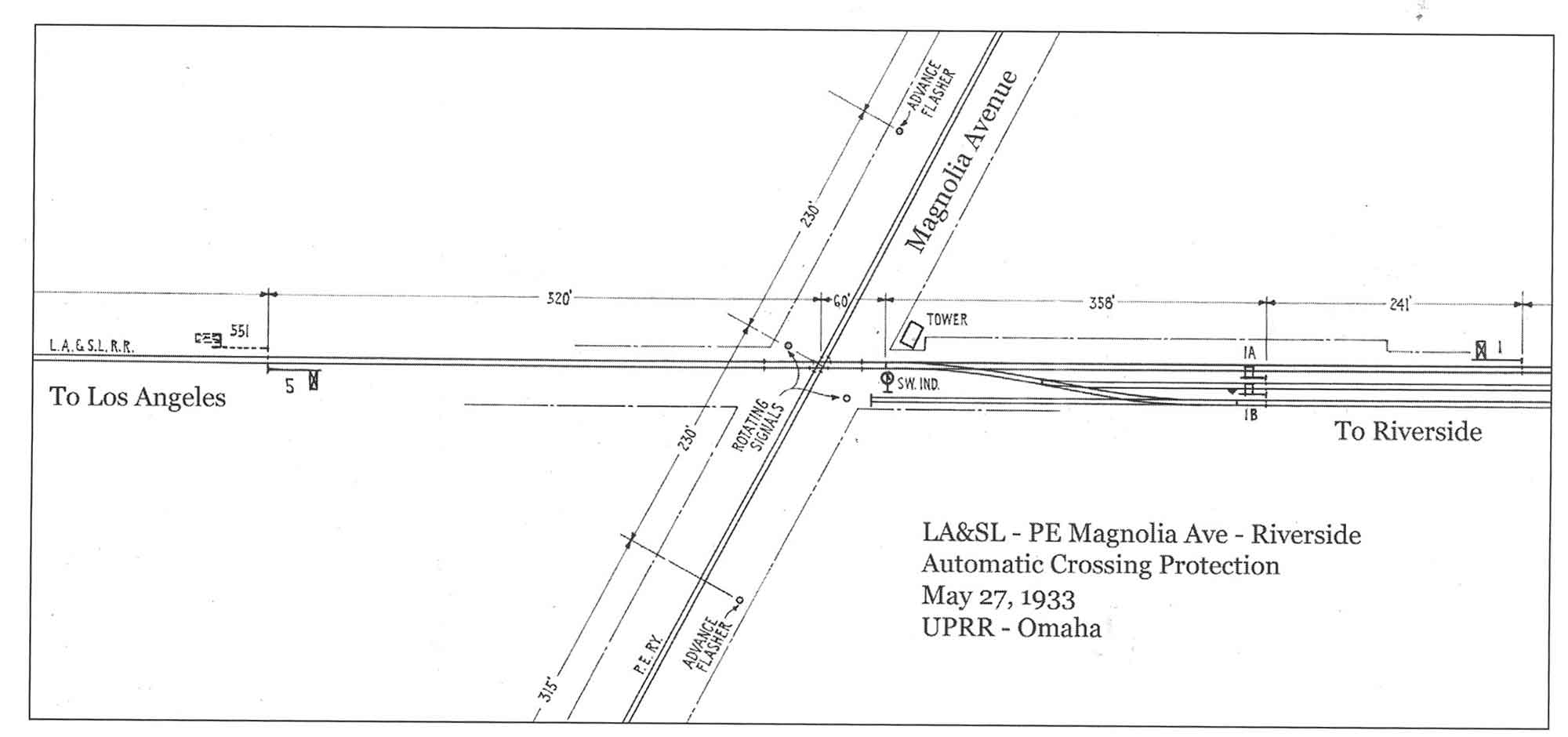

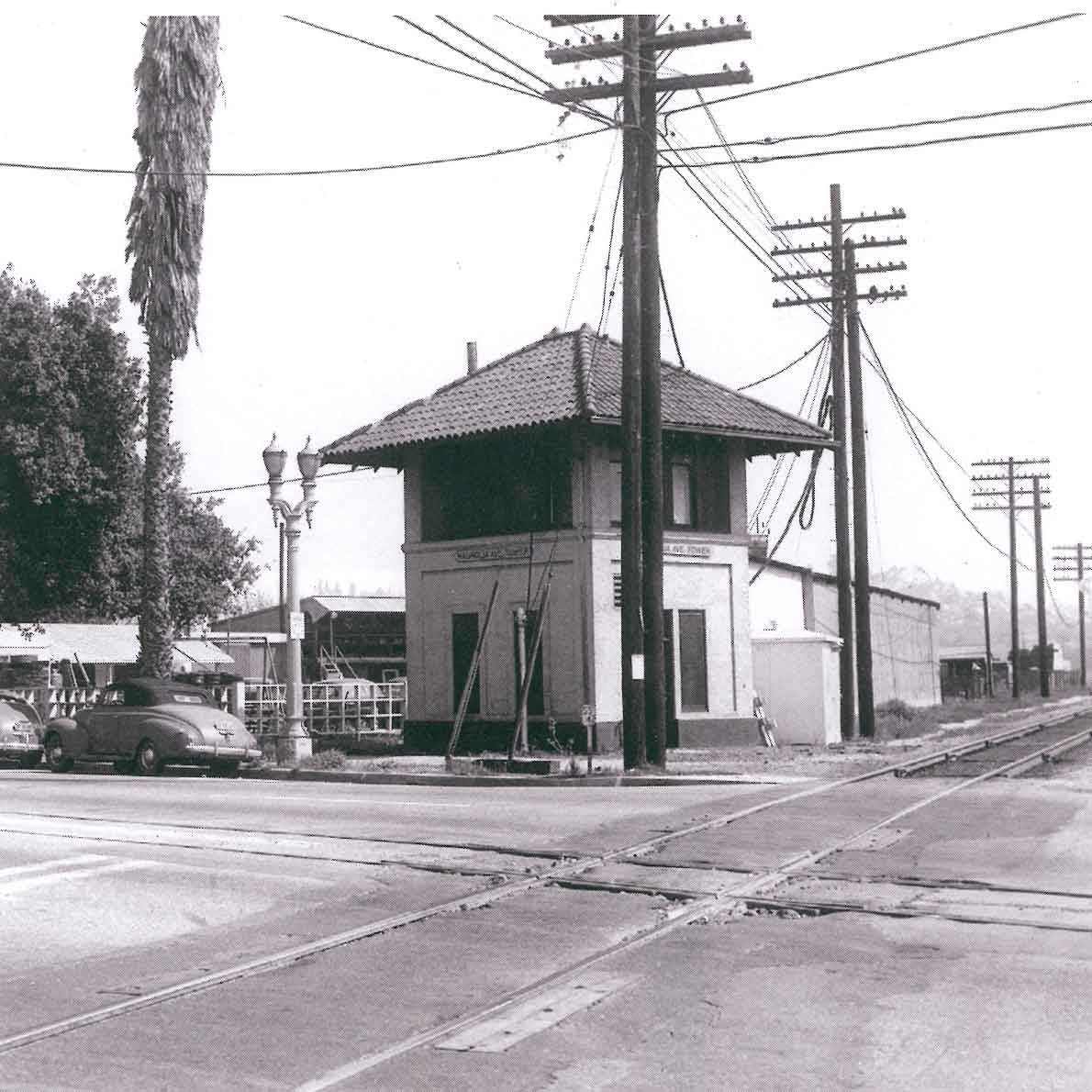

At that point, the California Railroad Commission required Pacific Electric to build an interlocking tower at the new crossing since they were relocating their tracks. The interlocking tower housed machines that were controlled by an operator or leverman. The operator would pull various levers, which would, in turn, align switches and signals for the tracks. Pacific Electric and Salt Lake shared ownership and the operating costs for the tower while Salt Lake managed the facility. The operations from the tower commenced mid-1916, and the Salt Lake moved their shelter shed one-tenth of a mile from Brockton Avenue to Magnolia Avenue.

In 1934, Union Pacific, which took full control of the Salt Lake Route in 1921, converted the rail line to automatic operation. The signal control circuitry was installed in the tower, which no longer needed to be manned.

Also, in 1934, another push was made to separate the Union Pacific tracks crossing from Magnolia Avenue. Mayor Criddle of Riverside strongly pleaded for funds because Magnolia was part of the state highway system, and several fatal accidents had occurred at this crossing. Nothing came of this plea during those Great Depression Years.

When Union Pacific switched from a block signal system to central traffic control in 1950, the tower was no longer needed and was removed. Block systems enable the safe operation of trains by preventing collisions. The basic principle is that a track is broken into sections or “blocks.” Only one train could occupy a block at a time. Centralized traffic control is a form of railway signaling that consolidates train routing decisions in a central location.

In May 1959, Pacific Electric moved its operations to Corona from Magnolia Avenue to the Santa Fee mainline, starting at Riverside Junction just north of downtown. In July and August 1959, Union Pacific and Pacific Electric removed the diamond interchange and the interlocking circuits at Magnolia Avenue, ending the decades-old crossing of the two lines.

Yet the crossing of the Union Pacific trains and the traffic on Magnolia Avenue continued to be an issue. Eventually, in 2011, the underpass on Magnolia Avenue, dropping down underneath the Union Pacific tracks, was finally built. The outlay cost of approximately $54 million was a far cry from the $100,00 estimated in 1914.

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every morning. For free!