A 12-Year-Old Folded Newspapers and Read Dan Bernstein's Column; Now He's Naming a Writing Room After Him

Bob Marshall's Typewriter Muse expands with a dedicated space honoring Riverside's longtime Press-Enterprise columnist.

A devastating misread order led to a high-speed collision between two trains on the Salt Lake Route, killing two and injuring six. Over a century later, echoes of the crash still reverberate through Riverside’s rail history.

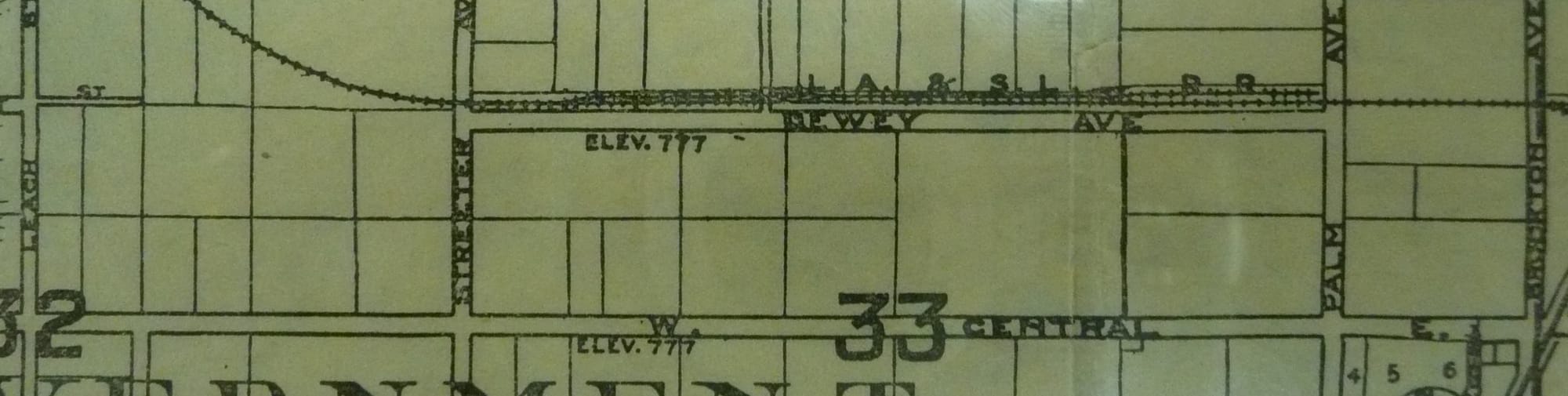

On June 6, 1905, a tragic train crash occurred on the Salt Lake Route Railroad. Senator William A. Clark built the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, also known as the Salt Lake Route. He wished to join the list of railroad barons and decided to construct his rail line from Los Angeles to the rich mineral areas of Utah. The first passenger train arrived in Riverside on March 12, 1904. The railroad entered Riverside over a newly constructed bridge across the Santa Ana River. When it was built in 1903, the bridge was the longest concrete bridge in the world. Over 120 years later, Union Pacific still runs numerous trains daily over this bridge and along the same line into Riverside and beyond. Soon after crossing the bridge at mile marker 52.3, trains round a curve near Streeter Street.

A little over a year later, disaster struck the new rail line through Riverside. Two dead and six injured—two of them seriously—was the sad story caused by the forgetting, overlooking, or misreading of orders by the crew of the Salt Lake Overland No. 1. The Overland was one of the Salt Lake Route’s mainline passenger trains, carrying travelers between the East and West. The early morning train passed westbound through Riverside at 5:23 a.m. on June 6, 1905. It was 30 minutes late and, having no passengers for Riverside, barely stopped at the station before pulling out for Los Angeles. A newspaper train, bringing early morning papers from Los Angeles, was due at Riverside at 5:45, meaning the Overland was on the newspaper train’s scheduled time as it left the station.

Whisked hot off the presses, the newspapers were bundled, thrown into trucks, and rushed to a central station—in this case, in Los Angeles. Working at top speed to meet critical departure times, teams would load the bundles into special train cars staffed with onboard workers who sorted them en route, much like postal clerks. Newspaper trains ran on tight schedules to bring news to numerous cities along their routes.

Salt Lake employees said the Overland’s orders were to take the switch at Dewey Avenue—a long siding stretching to Streeter Avenue—and wait there for the paper train. Had the Overland done this, it would have been about two minutes ahead of the paper train and safely out of its way. However, Engineer Gillott of the Overland passed the siding and, about half a mile beyond, came upon the paper train traveling nearly 60 miles an hour en route to Riverside. The engineers of both trains reversed their engines, gave despairing whistle blasts, and jumped. The firemen followed, and none of them were hurt.

In light of the crash, a reporter asked a veteran engineer how he would jump. His response: “In a hurry!” He went on to explain that he once had to jump headfirst out a window. If he’d taken the time to get off his seat and exit through the rear, he’d have been crushed between the engine and tender. He did suffer bruises and a broken leg—but he lived.

At the crash site, a sharp curve and a row of high eucalyptus trees obstructed the view ahead. Engineers could see about a quarter mile, but both trains were at full speed and had no time to stop after spotting each other. Engineer W.D. Gillott of the Overland later said he had read his orders as instructing a meeting at “Stalder”—about ten miles ahead of Streeter, the actual meeting point. “Stalder” and “Streeter” looked similar when hastily written, offering a plausible explanation for the tragic mix-up.

Veteran trainmen said that in all their years of experience, they had never seen two engines so completely reduced to scrap iron. The Overland—comprised of a mail car, express car, baggage car, smoker, chair car, tourist car, and five Standard Pullman sleepers loaded with Knights of Columbus members—was descending the steep grade from Pachappa Hill to the Santa Ana River. Gaining tremendous momentum, it struck the much lighter newspaper train and pushed it into the front of Overland engine #414 for at least 300 feet. Engine 102 of the newspaper train was driven halfway into the combination baggage car and smoker. Had passengers been on board, all would likely have died instantly. Brakeman Norman of the newspaper train was either in the smoker or on the platform—he was crushed in the wreckage and killed. Head Brakeman T.E. Carey of the Overland also perished instantly.

When the trains collided, the crash was heard in Riverside, several miles away. The first shock was followed by the eerie hiss of escaping steam as both boilers burst into the still early morning air. One observer noted that the old-fashioned mail car “was stripped into kindling wood and stood out as a striking evidence of the wisdom of good construction and the risk of cheap construction.”

At the inquest, L. House, conductor for Overland No. 1, testified that the written orders he received from the telegraph operator at Riverside Junction read: “No. 6, engine No. 102 will meet No. 1, engine No. 6 at Streeter Avenue,” and this is what he delivered to Engineer Gillott. However, House also admitted that the usual meeting place for the two trains was Stalder, not Streeter. Since Overland No. 1 was running late, there was no time to safely reach Stalder before the newspaper train's arrival.

Starting with timetable No. 21, dated December 19, 1905, the Stalder depot was renamed Wineville—only six months after the tragic wreck. No official order has been found explaining the change, but several accounts and articles by local historians later linked the renaming directly to the wreck. Erwin Gudde, writing on California place names, stated: “The original name, Stalder, for an old settler, was changed to Wineville when the Charles Stern Winery was built there.” However, the winery was constructed in 1903, when the station was already called Stalder. The name change came after the crash, indicating it may have played a role. The rise of grape growing in the area likely helped solidify the choice of “Wineville.” The local post office followed suit by officially adopting the Wineville name in February 1908.

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every morning. For free!