Could You Recognize a Blood Clot? A Heart Rhythm Problem? Riverside Cardiologists Break It Down

American Heart Month is ending — but Riverside Medical Clinic's cardiology team wants these warning signs to stick with you.

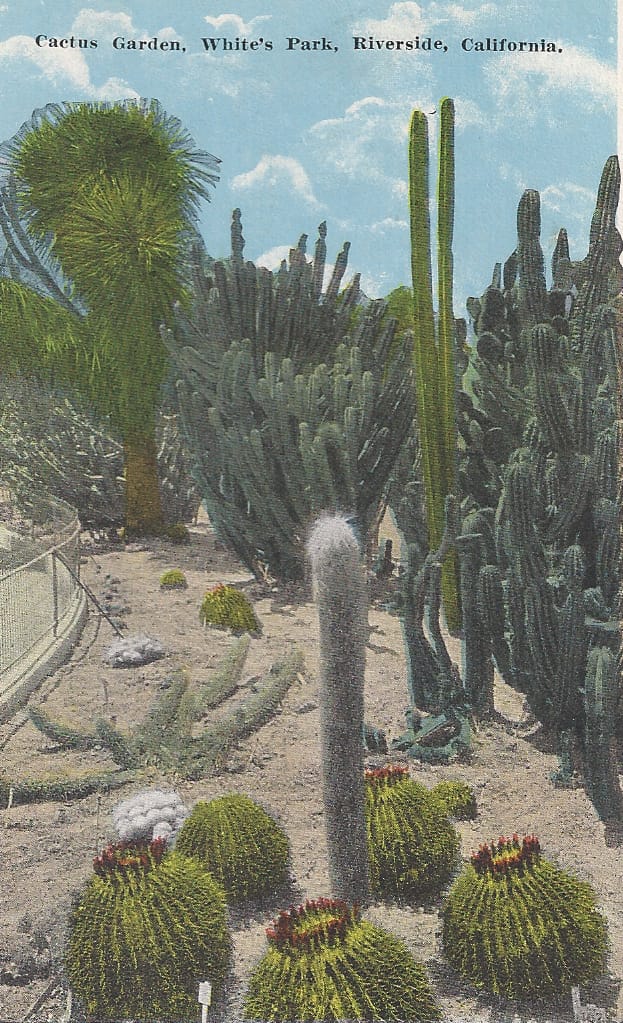

Once hailed as a world-class botanical marvel, the White Park cactus garden has faded from view—but new plans aim to restore this historic Riverside treasure to its former glory.

Driving up to my home in Riverside, you might be struck by the abundance of succulents and cacti in the front yard. My wife loves succulents, and years ago, we converted the yard from grass—which needed watering and mowing—to a succulent garden, which requires less care. Our youngest son and a friend did the digging and significant planting. They even installed a dry streambed with a bridge. Over the years, some cacti have grown quite tall and have been trimmed back numerous times.

We cannot claim to have the first Riverside cactus garden. Many others have transformed their yards into beautiful arrays of succulents. The oldest example of transplanting and creating such a garden was the one transplanted into the downtown Albert S. White Park.

Established in 1883, it was the first park in Riverside. Within the original mile square, it was initially called City Park. In 1899, City Park was renamed White Park in honor of Albert White, an early park commissioner who was instrumental in developing the park.

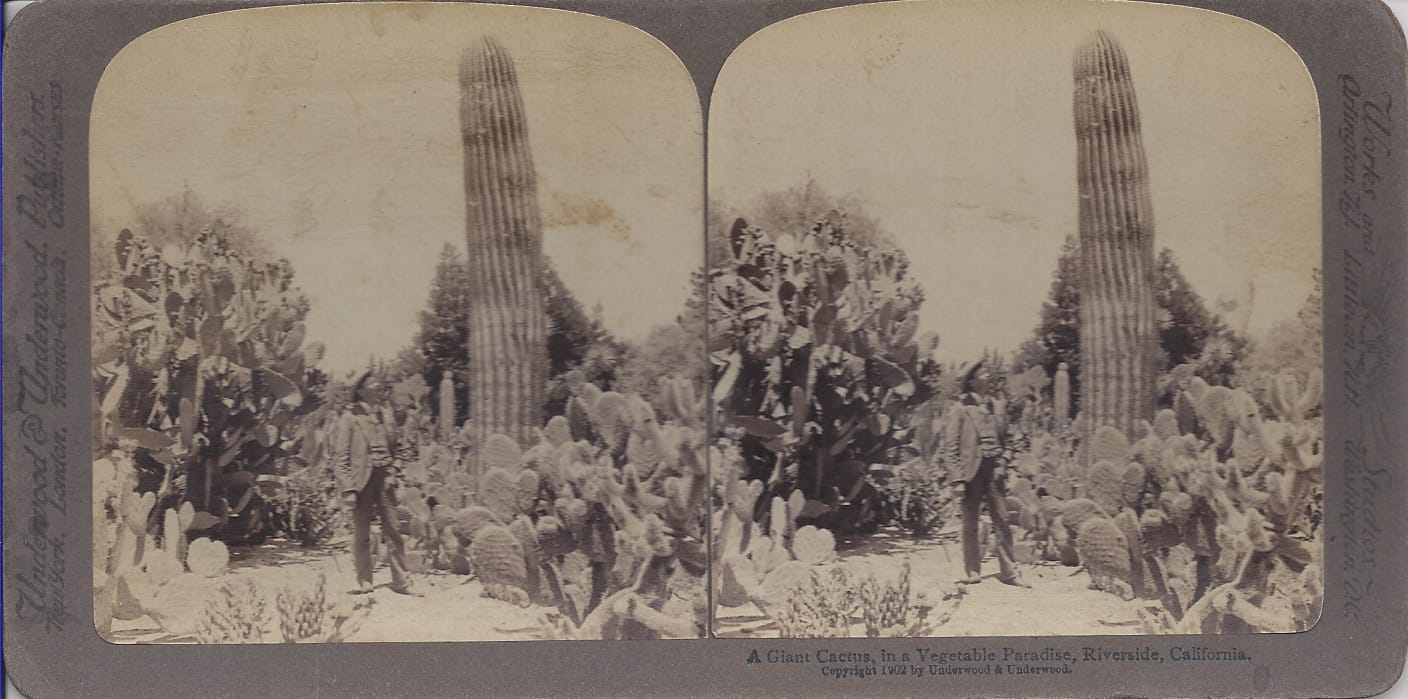

However, another name that needs to be included in the development of White Park is horticulturist Franz Hosp. In August 1888, the city hired Hosp to develop plans for the ornamentation of City Park at a cost of $2,500. By 1893, a reporter noted that the park's most unique feature was Hosp’s miniature desert, which featured every variety of cactus known in California. The park contained more than 200 different varieties of cactus. He returned with cactus from excursions into the Colorado Desert and the desert near Twentynine Palms. One was a 12-foot-tall giant cactus (Cereus giganteus). As a landscape architect for the Santa Fe Railroad, Hosp traveled along the railroad's lines throughout the Southwest and brought specimens home.

Some of the many species that Hosp brought to Riverside by May 1893 were cotton top cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus) from Twentynine Palms, California barrel cactus (Echinocactus cylindricus) from Morongo Pass, prickly pear (Opuntia) from near Morongo, banana yucca (Yucca baccata) from the Colorado Desert, and pin cushions (Mammillaria) from Arizona.

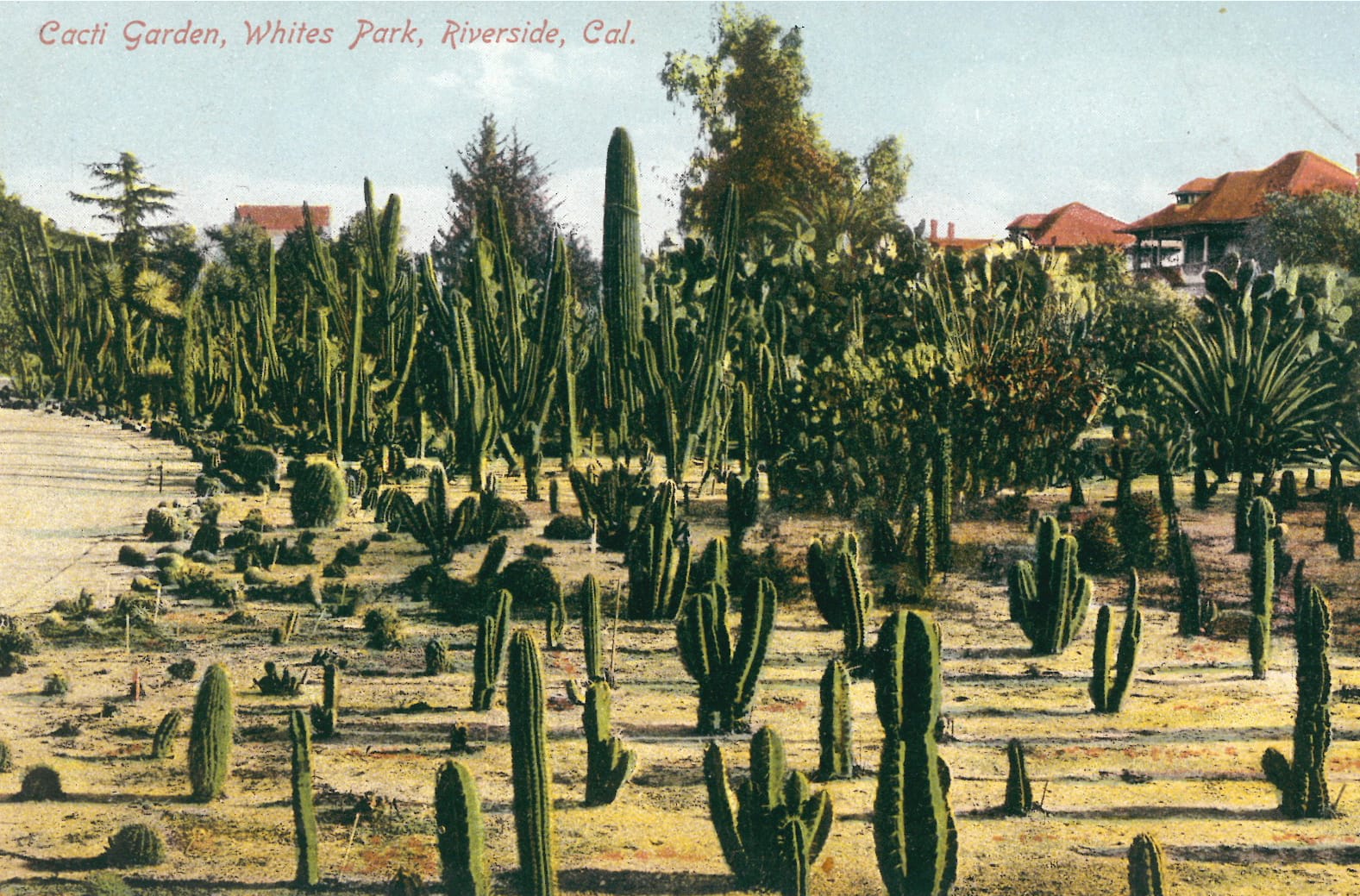

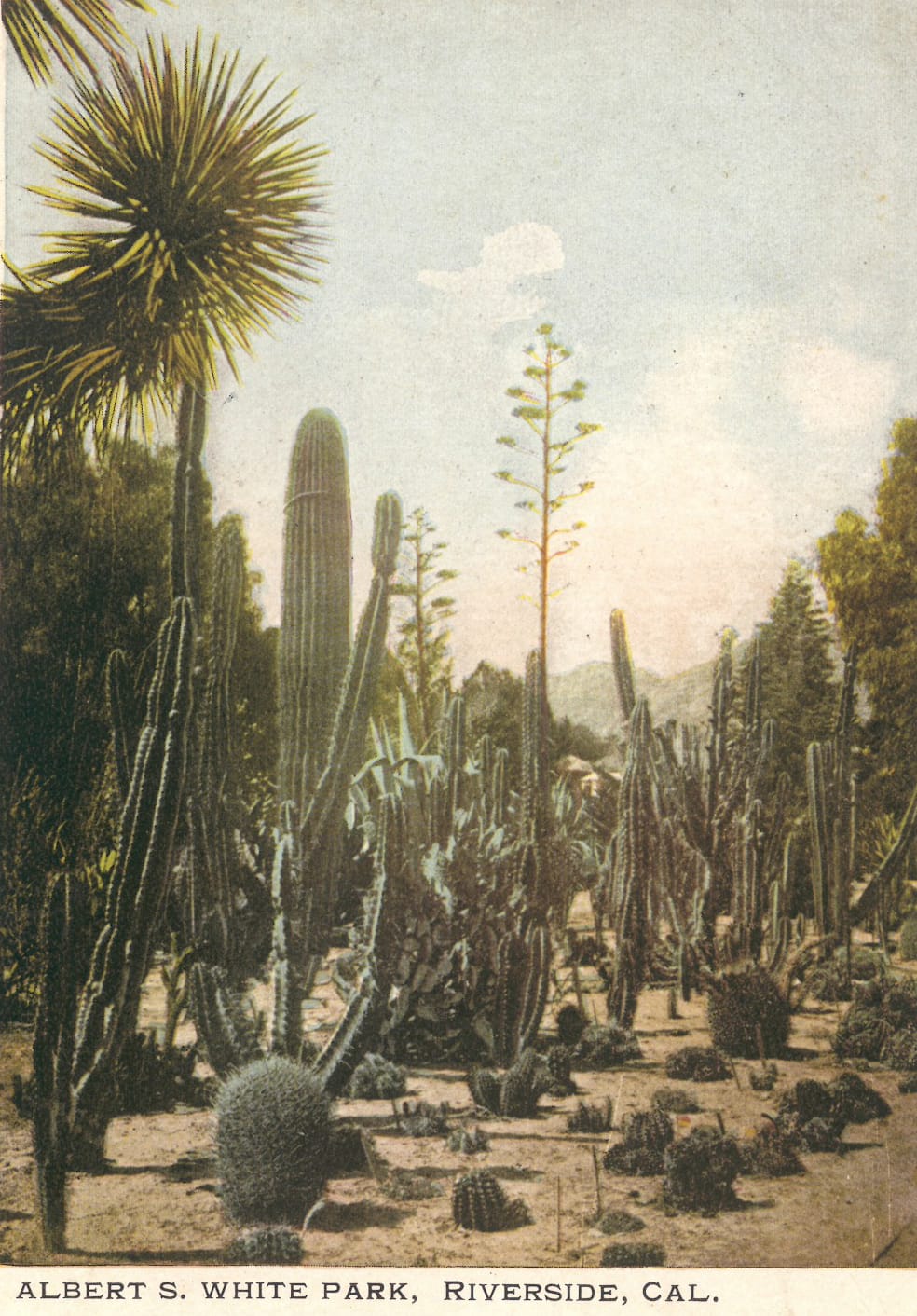

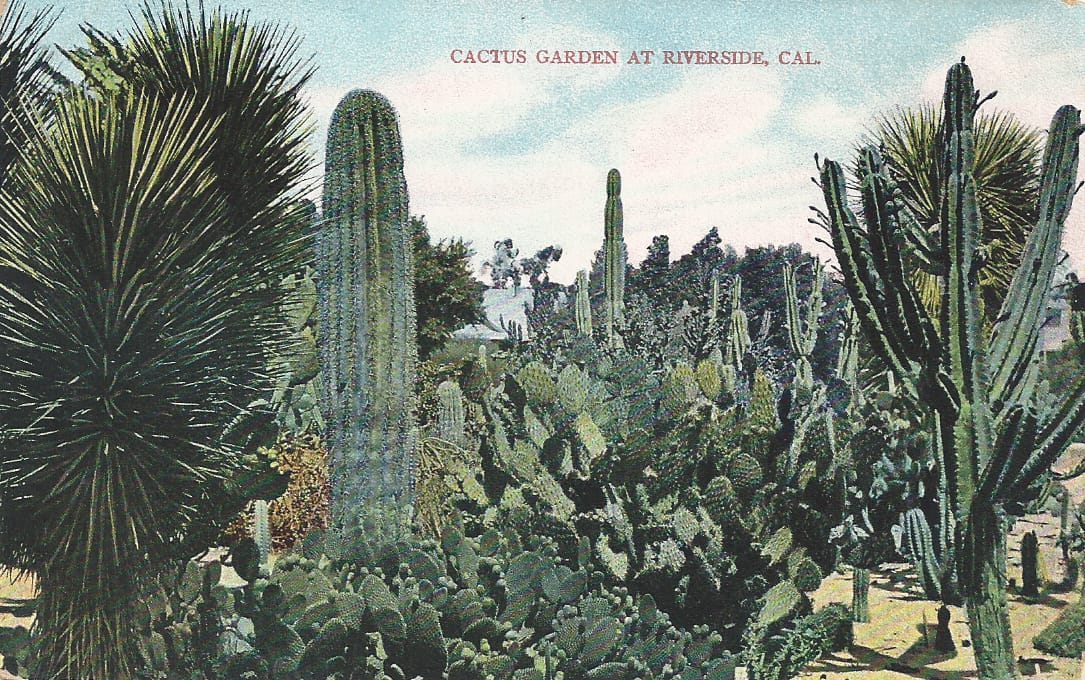

Two Postcards of Cactus in White Park. (Author’s Collection)

At the end of 1904, Albert White announced that a spineless prickly pear cactus had grown in the park for almost 10 years. George Frost accused White of pulling out the spines, but White denied it. A U.S. Department of Agriculture representative visited the park, examined the plants, and took away some samples for study. A local reporter asserted that Luther Burbank could learn some propagation lessons from Albert White.

Two Postcards of Cactus in White Park. (Author’s Collection)

Riverside residents and visitors dropped in to White Park to view what was lauded as one of the most extraordinary cactus collections in the United States—and some said, the world. Stokes Bennett of Riverside, in 1913, wrote an article for The Christian Science Monitor extolling the garden for its great variety of plants. He pointed out that Riverside’s climate allowed these plants to thrive year-round. Two years later, in the July 1915 issue of Sunset Magazine, an article featured the wonderful exhibit of cactus growing in White Park. The author said it was the best collection of its kind in the world. She paid tribute to Park Superintendent Harry Dunbar, who had created a spectacular Christmas cactus by grafting an ordinary Christmas cactus onto a taller upright cactus.

From left to right: Photo of Two Couples Posing Among the Cactus in 1904, Photo of Four Women Posing Among the Cactus in 1910. (Author’s Collection)

By the 1930s, a fence was erected along the walkway separating park visitors from the cactus. The fence was intended to diminish the pilfering of the valuable plants. In May 1933, Park Superintendent A.S. Cooper worked on improving and bringing the White Park cactus garden back to the forefront. Twenty-five truckloads of new cactus soil were brought in, along with approximately 100 plants, including 10 new specimens for the park. Cooper sent a crew to the Pushawalla District near the Colorado River, where work on the aqueduct made abundant cactus available for transplanting. An example of the variety they brought back was a new cristate barrel cactus with three crests or heads, one of which weighed about 500 pounds. Another special find was a 9-foot-high pipe organ cactus.

Upon the recommendation of Park Superintendent George W. Rush, the park board decided in August 1942 to remove and transplant many species of cactus to different locations. At that time, the cactus gardens comprised about one-third of the park. The reasons behind this move were the loss of interest in cactus, many more unusual species having been stolen over the last decade, and the acreage being seen as better used as grass areas for park visitors and picnickers. Head of the park board Archie Shamel was so proud of the many rare varieties that he had labels describing them and mentioning how rare they were. This prompted visitors to dig them up and take them home clandestinely.

By the early to mid-1990s, White Park was called a “Hooverville” (a term used during the Great Depression to describe shantytowns or encampments built by homeless people). In April 1997, the park department erected a fence around the park and closed it for an 18-month renovation. As with many projects, the work stretched out and lasted four and a half years. White Park celebrated a grand reopening on Friday, Nov. 16, 2001.

The newly redeveloped park included several themed gardens: African, Asian, Mediterranean, palm, rose, hummingbird, and most importantly, a cactus garden. Small compared to the original, which took up one-third of the park, there was a hint of the historical portion created and nurtured by Franz Hosp and Albert White. The cactus garden is located on the park's south side along the fence near the side entrance to Hidalgo Street.

By May 2025, neither White nor Hosp would recognize White Park. The once-splendid, world-class cactus garden has been reduced to a handful of specimens in a small, bare area.

However, according to Pamela Galera, director of Riverside’s Parks, Recreation, and Community Services Department, plans to revitalize the cactus garden are in the near future. Join me in watching for this exciting development.

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every morning. For free!